Does the First Amendment’s free speech clause prohibit criminal prosecution for lying in a political campaign ad? That issue came before the United States Supreme Court yesterday in Susan B. Anthony List v. Driehaus, a case arising out of Ohio.

Ohio is one of a few states with a law that criminalizes making an intentionally false statement about a political candidate. In 2010, then-Congressman Steven Driehaus filed a complaint under that law with the Ohio Elections Commission against advocacy group Susan B. Anthony List, which had made several allegedly false statements about his vote in favor of the Affordable Care Act. (The Ohio Elections Commission has the authority to recommend criminal prosecution under the law). The Elections Commission recommended prosecution, but Driehaus dropped his complaint after he lost his re-election bid, so no prosecution occurred. Nevertheless, Susan B. Anthony List sued in federal court, claiming Ohio’s so-called “truth-in-politics” law violated the First Amendment. The case was argued yesterday in the Supreme Court.

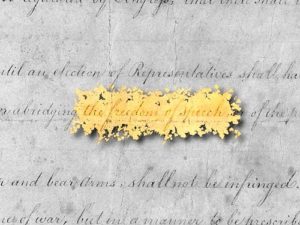

Technically, the question before the Court is not the constitutionality of the law, but whether the challengers of the law have the right to sue, as they were not actually prosecuted. According to news reports from the oral argument however, the Justices appeared very skeptical about law’s constitutionality. Multiple Justices expressed concern about the chilling effect of public officials deciding whether people should be criminally prosecuted for engaging in political speech. That concern is unsurprising, given the potential for abuse and the central importance of political speech in constitutional case law. Free speech jurisprudence has always treated political speech as deserving special protection. In fact, even distasteful, insensitive, or unfair political speech is generally entitled to First Amendment protection.

As an aside, Ohio common law already prohibits false statements of fact that harm another’s reputation. It is called defamation. Such actions have been held permissible by the Supreme Court. However, the Court has long held that public figures such as politicians have to satisfy a particularly high burden of proof when suing for defamation because of the right to free speech. Although not entirely clear from the oral argument, the availability of a defamation action could ultimately play into a decision on constitutionality of the law.

Because the question before the Court is really a threshold one—whether Susan B. Anthony List can sue now or must wait for actual prosecution—it is expected that the Court may not explicitly rule on the merits. Instead, it is expected that the Court may send the case back to the Court of Appeals to do so first. If the oral argument is any indication though, it is possible the Court was so disturbed by the law that it will send a strong signal that the law violates the First Amendment. Thus, while Ohio’s truth-in-politics law has the well-intended goal of prohibiting people from misleading voters in elections, its future is very much in doubt.

Leave a Reply